In This Issue: From The Skittles Room Eman Sawan's Annotated Games from the Olympiad, by GM Johan Hellsten Endgame Corner, by IM Silas Esben Lund Revisiting Frank Marshall, in an Enjoyable New Book, by Jeffrey Tanenbaum Chess Toons En Passant Problems, Problems, curated by Alexander George Editor's Note

Welcome back, fellow chess players, to this edition of the Marshall Chess Club's fortnightly bulletin, The Marshall Spectator.

We are thrilled to launch a new series of Chess Workshops for Kids at our historic club. See details below and sign up for the few remaining spots before they sell out.

In other exciting news, The Marshall Chess Club is excited to announce our partnership with ChessMood, an online chess training platform that helps players improve their game with courses, training, and other resources. Using the link below, members will receive a ChessMood membership free for one month if they claim it between October and November! Renewing members will also receive one month free. People who sign up for a ChessMood membership will receive a discount and help support the club.

Get your one month free here and view some ChessMood Success Stories here.

Looking ahead on the calendar, the Blitz and Rapid Championship is scheduled for the second week of October, and is certain to be a popular event. The new format features two separate events with a combined points for prizes structure. We look forward to the event and hope to see you there.

Another exciting event that is taking place this week is the Ibero-Americano Absoluto, in Linares, Spain. And what’s just as exciting as the games for us is that one of our very own Arbiters, IA Oscar Garcia, is the Chief Arbiter for the elite international event.

If you speak Spanish, you can watch this interview with him, where he even talks about the growth of popularity in chess post-pandemic and the Marshall Chess Club in particular around the 5:40 mark.

Over the last two weeks we have had a plethora of events for our members to play in.

The Wesley Hellner Action on September 26 had 45 players registered and was won by Vladimir Bugayev, IM Jay Bonin, and Levi Fogo Esquivel who scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $122.33 each. Jephson Mathews scored 3 out of 4 to win $85, while Justin Dalhouse and Krishnan Warrier scored 3 out of 4 to win $42.50 each.

The Thursday Open that concluded on September 26 had 20 players registered and ended with 4 players tied with 4 out of 6 each. Aleksandr Gutnik, Nirupam Kushalnagar, George Berg, and Nicholas Marino won $100.25 for their tournament performance. Daniel Ray scored 3.5 out of 6 winning $67, and Benjamin Eppel scored 3 points winning a class prize of $34.

The Rated Beginner Open on September 22 had and even 40 players registered and was won by Theodore Stoffa Kowakski and Seokwoo Lee who scored a perfect 3 out of 3 to win $250 each.

The Monthly Under 1800 on September 22 had 26 players registered and was won by Cyril Chua who scored 4.5 out of 5 to win the $417 first place prize. Gregor Bonnell and Julian Spedalieri scored 3.5 out of 5 to win $136 each. Ari Hoffman scored 2.5 points to win a class prize of $125, while the following players scored 3 out of 5 to win $31.25 each: Kirill Tsydypov, Yidong Chen, Arman C Jain, and Matthew Dinglasan.

The Monthly Under 2400 on September 22 had 65 players registered and was won by James Marsh, who scored 4.5 out of 5 to win $1,084. IM Jay Bonin and Linxi Zhu scored 4 points to win $352.50 each. Rishith Bhoopathi, Luis-Joshua Casenas, and Noah Gillston scored 3.5 points to share in a class prize, winning $108.33, while Rocco Jan Degeest, George Berg, Nivaan Shrivastava, and Eden You scored 3.5 out of 5 to win $81.25 each.

The Morning Masters on September 21 had 9 players registered and was won by Aditeya Das, who scored a perfect 3 out of 3 to win $68. Dominic Paragua, Miles Hinson, and Rohan Lee scored 2 out of 3 to win $15 each.

The Under 2000 Morning Action on September 21 had 55 players registered and finished with 6 players getting a perfect 3 out of 3 score. Arianna Lu won a class prize of $207, while the following 5 players won $96.40 for their 3 out of 3 score: Jaime Jariton, Jack Boyer-Olson, Jan Buzek, Somario Blagrove, and Owen Mak.

The Friday Rapid on September 20 had 17 players registered and was won by WFM Chloe Gaw and IM Justin Sarkar who scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $63.75 each, while the following 4 players won $21.25 for their performance in the Rapid event: Noe Solorio Valderrama, Anna Radchenko, Chris Weldon, and Matt Schwartz.

The Wesley Hellner Action on September 19 had 43 players registered and was won by Bryan Weisz, who scored 4 out of 4 to win $158. Vladimir Bugayev and IM Jay Bonin scored 3.5 out of 4, winning $92 each, while Sravan Mokkala won a class prize of $39.50 for their 3 out of 4 score. Finally, the following 4 players won $19.75 for their 3 out of 4 performance: Andrew Colwell, Dominic Paragua, Levi Fogo Esquivel and Mitchell Stern.

The Marshall Masters on September 17 had 22 players registered and was won by GM Andrew Tang, who scored 4 out of 4 to win the $293 first place prize. IM Jay Bonin scored 3.5 out of 4 to win clear second and the $201.67 prize, while FM Liam Putnam won the $91.67 3rd place prize. Joshua Block, Chenxuan Ling, Ethan Kozower and FM Jonathan Subervi won $18.33 each for their 2.5 out of 4 score in the Masters event.

The FIDE Monday Open that concluded on September 16 had 51 players registered and was won by WFM Abby Marshall and Max Mottola, who scored 5 out of 6 to win $425 each. Whitney Tse won a $170 class prize, scoring 4 out of 6. Mubassar Uddin and Tim Shvarts scored 4.5 out of 6 to win $85, while David Deng, David Timmerman and Naveen Paruchuri won $28.33 each for their 3.5 score.

The Monday Under 1800 that concluded on September 16 had 32 players registered and was won by Cameron Hull, who scored 5.5 out of 6 to win $207. Matt McColgan and Jack Murtagh scored 4.5 points winning $129.50 each, while the following 3 players won $52 for their 3.5 out of 6 score: Thyge Knuhtsen, Thomas DeDona and Johanna Soto.

The Rated Beginner Open on September 15 had 44 players registered and was won by Robert Haddad, Joseph Fermin, Teejan Jalloh and Vitaly Shaydurov who scored 3 points to win $137.50.

The Sunday Game 50 Under 1600 on September 15 had 52 players and was won by Nicholas Kan, who scored a perfect 4 out of 4 to win $312. Mark Xu scored 3.5 points to win $156, while Kirill Tsydypov and Conrad Kassin scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $104 each.

The Sunday Game 50 Open on September 15 had 34 players registered and was won by GM Mark Paragua, who scored a perfect 4 out of 4 to win $198. Jack Boyer-Olson scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $132, while Raza Patel scored an even 3 points to win $99.

The Morning Masters on September 14 had 6 players registered and was won by Matheu Jefferson, who scored 2.5 out of 3 to win the $45 first place prize. Robert Olsen, Aditeya Das and Daniel Wang scored 2 points out of 3 in the event to share in the remaining prize funds, winning $10 each.

The Saturday Game 50 Under 1800 on September 14 had 48 players registered and was won by Arjun Sarin Pradhan, who scored a perfect 4 out of 4 to win the $282 first place prize. Anthony Li, Brian Gilbert, Saloni Varma and Manuel Najera scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $82.25 each.

The Saturday Game 50 Open on September 14 had 37 players registered and was won by Elliot Goodrich and IM Jay Bonin who scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $185 each. Tim Shvarts, Jeremy Yoon and Matt Chan scored 3 points to win $37 each.

The Under 2000 Morning Action on September 14 had 35 players registered and was won by Aiden Amin, Kyle Clayton, and Mason Welch, who scored a perfect 3 out of 3 to win $102.33 each. The following 5 players won a class prize of $26.40 each for their 2 out of 3 score: Manish Suthar, Kenny T Bollin, Alexander Soll, Alexander Rosenberg, and Liam McPeake.

The Women and Girls’ Open on September 13 had 25 players registered and concluded with Aileen Lou, Alyssa Zhu, and Lily Aponte all scoring a perfect 3 out of 3 to win $75 each.

The FIDE Blitz on September 13 had 64 players registered and was won by GM Maxim Dlugy, who scored 8 out of 9 to win $320. GM Andrew Tang and FM Liam Putnam scored 7 out of 9 to win $120 each, while Linxi Zhu scored 6.5 points to win $80. Wyatt Wong also won $80 for his 6 out of 9 score, while the following 4 players won $20 each for their

5 out of 9 score: Isaac Statz, Ethan Kozower, Viyaan Doddapaneni, and Corin Gartenlaub.

The Wesley Hellner Action on September 12 had 48 players and was won by IM Jay Bonin and GM Mark Paragua, who scored a perfect 4 out of 4 to win $141 each. Vladimir Bugayev scored 3.5 out of 4 to win $85, while Joseph Otero also won $85 for his 3 out of 4 score. The following 5 players won $17 for their 3 out of 4 score as well: Ryan Thurlow, Miguel Garcia, Jack Klein, Andrew Colwell, Daniel Frank Johnston.

We look forward to seeing you at the club soon!

Eman Sawan at the Olympiad, by Katie Dellamaggiore with game annotations by GM Johan Hellsten

Eman Sawan is a 17-year-old Palestinian chess player. I met her and her teammates in 2022 while filming at the Chess Olympiad in Chennai, India. At the time, it was a massive feat for the entire team to gather in Chennai because international travel for Palestinians living under occupation is often restricted. As I filmed with Eman and her mother, Rasha, it was clear that Eman was not just a rising chess talent but a kind, passionate, and hardworking teenager with big dreams despite the many obstacles that stood in her way.

Eman remembers watching her father and grandfather play chess as a young child, and she felt excited when her father taught her how to play. That same year, she entered her school's chess championship and won. Now, Eman is a high school junior living as a Palestinian refugee in Jordan and must balance her studies with chess, all while praying for family and loved ones who are in the midst of brutal conflict in Gaza. While Eman was fortunate to live in Jordan, life as a Palestinian refugee is far from easy. She can't play in the same tournaments as Jordanian chess players, and her family faces financial challenges, making coaching opportunities and international tournaments even more difficult. However, members of the global chess community, including the Marshall Chess Club, rallied behind a GoFundMe that her mother started, to help pay for coaching and chess-related travel.

While working with GM Johan Hellsten over the past year, Eman increased her rating by over 200 points, achieved the Women FIDE Master title, and was able to travel to the 2024 Olympiad in Budapest - where our film team met up with her again. Despite sharing heartbreaking stories of chess friends in Gaza who have been badly injured or killed in the ongoing war, Eman and her teammates were excited and proud to be once again playing chess on the world stage. And all of their hard work paid off. Eman played her best chess with a final score of 8/9 and a rating performance of 2202. She is an incredibly resilient young woman who, in many ways, represents the impact chess can have on a young person's life. I'm excited to keep documenting her story for an upcoming documentary called "Queen's Castle" and inspire other young women from around the world to keep fighting for their dreams.

You can play through the below games with annotations by GM Hellsten here.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

De Blecourt Sandra vs. Sawan Eman

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 Just like legendary Judit Polgar, Eman likes to counter 1.d4 with the King's Indian Defense. Actually I can't think of a better opening choice for attacking players! The fact that chess engines don't rate this opening highly has probably made it less popular nowadays than in the last century, but one nice thing about the KID is that White can't easily trade down to a dry position in any line; there will always be imbalances for Black to work on.

3.Nc3 Bg7 4.e4 d6 5.Bd3 A solid sideline, championed by Italian GM Luca Moroni, among others. Every move has its pros and cons, here we can see that the d4-pawn is less secure than in other KID lines, which explains Black's reaction.

5…O-O 6.Nge2 Nc6 7.O-O e5 8.d5 Nd4 ( 8...Ne7 preparing ...Nd7 and ...f5 is also playable, but it's usually nice for Black to plant a knight in the center, similar to the Pillsbury knight on e5 with reversed colors and flanks.)

9.Nxd4 exd4 10.Ne2 ( 10.Nb5 is well met by Re8, e.g. 11.Re1 a6! 12.Nxd4 Nxd5 13.cxd5 Bxd4 with roughly equal play. White has more space but Black's dark squared bishop is the strongest of the four. )

10…Qe7!? ( 10...Re8 looked natural, just like in the previous note. However, if Black one day achieves the ...f5 pawn break, then the rook will be better placed on f8. Furthermore, the other rook can join the battle sooner if the queen gets off the 8th rank.)

11.f3 (11.Nxd4 Nxe4 is no real success for White.)

11…Nd7 A move with various functions: the d4-pawn is protected, ...Ne5(c5) is prepared, and Black gets ready for...f7-f5 at some point.

12.Bc2 ( 12.Bf4 was played in the game L.Moroni - J.Vakhidov, Sharjah Masters 2023, which continued c5 13.Qd2 Ne5 14.Bg5 f6 15.Bh4 g5 16.Bg3 Nxd3! Why give up the strong knight for the passive bishop, one might ask. Well, as the old saying goes, don't look at what leaves the board, but what stays there! After 17.Qxd3 f5! Black is favored by the fact that their light squared bishop, a key player in many KID attacks, can't be traded off anymore. Following 18.b4 b6 19.bxc5 bxc5 20.Be1 h5 21.Bd2 h4 Vakhidov had a promising attack on the kingside, which he later converted into a win.)

12…Qf6 ( 12...c5!? 13.dxc6 bxc6 14.Nxd4 Ne5 might have been the choice of Judit Polgar, who rarely shied away from giving up a pawn for the initiative. However Eman's move is reasonable too; after all, that d4-pawn is quite annoying for White.)

13.Rb1 De Blecourt prepares b2-b4, a move which would have failed both tactically (13...d3) and positionally (13...a5) if played at this very moment.

13…c5 Allowing b2-b4 and Bb2 would leave the d4-pawn in danger. 14.dxc6 bxc6 15.b4 c5 Every move has its pros and cons - Black secures d4 but also weakens d5, which explains White's reply.

16.Nf4! Nb6 17.Bd3 Bd7 Development can't be wrong. 18.Qb3 ( 18.b5 preparing a4-a5 is well met by a6! clearing the a-file for counteraction.)

18…Ba4 Eman is preparing to take on b4 and later regroup the knight to c5, which explains why the bishop should leave d7. 19.Qa3 cxb4 20.Rxb4 Bc6 21.Nd5 ( 21.Bd2 seems more flexible, although after 21…Nd7 it's not easy to find an active move for White besides 22.Nd5 anyway.)

22…Bxd5! Of course! The knight is smarter in this pawn structure with a stronghold on c5. 22.cxd5 Nd7 23.Bd2 (23.Bb2 targeting d4 looked natural, although after a5! White can't take on d4 in either way - 24.Bxd4? fails to 24...axb4, while 24.Rxd4?! Rab8 (24...Qf4 at once allows 25.Bb5! Bxd4+ 26.Bxd4 turning the tables) 25.Ba1 Qf4 leads to tactical issues on the dark squares, e.g. 26.Rc4 Qe3+ 27.Kh1 Bxa1 28.Rxa1 Ne5 29.Rc3 Rfc8! when the pin on the 3rd rank alongside the back rank motif is too much for them to handle. Here we can see another benefit of Black's 21st move: a "good knight vs. bad bishop scenario" can be reached after a subsequent trade of the dark squared bishops.)

23…Nc5 24.Rfb1

White has completed development, although it's not really clear what their next step is, with the c5-knight seriously restricting their pieces. Eman now resorts to an idea which is sometimes attributed to chess engines, although the masters from the good old days certainly knew about it as well. For instance, Bent Larsen once said something like "when you don't know what to do, push a rook pawn!". I'd also like to mention the game L.Portisch - L.Christiansen, 1982, where the Hungarian GM carried out a similar idea as White in a Gruenfeld-like structure, and went on to win in beautiful fashion.

24…h5! No matter what happens next, this just has to be a useful move - any tactical surprises on the 8th rank are avoided, while attacking possibilities with ...h4-h3 are created. If White ever meets ...h5-h4 with h2-h3, then their whole kingside structure is weakened on the dark squares.

25.Bf1 h4 26.h3?! The chess engine approves of this move, but as humans approaching time trouble I think we should rather avoid it, since it forces us to be constantly on our guard against attacking ideas on the h2-b8 diagonal. ( 26.Qc1 preparing 27.Bg5 comes to mind, e.g. 26…h3 27.Bg5 Qe5 28.Qf4!? on the topic of defensive exchanges.)

26…Rfc8 Such moves, seizing an open file, are rarely wrong. It's also interesting to notice that Black suspends the ...f5 plan for now, since they already have enough targets on the kingside.

27.Rc4 Qe7 28.Qc1 ( 28.Bb4 Be5! preparing ...Qg5-g3(f4) shows one function of Black's 27th move.) 28…Bf6 Ruling out 29.Bg5. For the moment Black's kingside attack doesn't really progress, on the other hand - unlike White - they still have one more piece waiting to join the battle...

29.Rb5 Rab8! Suddenly White's game isn't that easy. Apart from their dark square weaknesses, they also have to think about the open b-file, the passed d-pawn and so on.

30.Qb1 Rxb5 31.Qxb5 Qe5! Eman notices that since White's queen left its defensive post on c1, they can't reply 32.Bf4 anymore.

32.f4? Desperation in a difficult position. (32.Qb2 bringing back the queen to the defense was called for, when after 32…Qg3 33.Qc1 Be5? White is just in time for 34.f4! Black could consider something like 32...g5 instead, preventing f3-f4 in advance. I'd certainly take Black's side here, but the battle is far from over.)

32…Qxe4 33.Rc1 Qxd5 With two extra pawns and a more active position, the rest is child's play for Eman. 34.Bc4 Qc6! Even KID players welcome queen trades when they're two pawns up! 35.Qb1 Kg7

Blundering 36.Qxg6+ would have been tragic.

36.Re1 d5! Pawns helping pieces - Black gets a nice outpost on e4 for the knight.

37.Bb5 Qb6 38.f5 Ne4! The threat of ...d3+ spells the end for White.

39.fxg6 Muddying the waters is generally a good idea in difficult positions.

39…Nxd2 40.Qf5 Qc5! ( 40...d3+ 41.Kh1 Ne4 is what chess engines would play, since they can quickly calculate that the attack pays off after giving up the c8-rook. In contrast, for humans with a (presumably) winning position it's advisable to keep things as simple as possible, especially on move 40!)

41.gxf7 Having sorted out the time control (move 40), Eman now takes her time to calculate the final complications, making sure that White won't have a perpetual.

41…d3+ 42.Kh1 Ne4!

43.Qg4+ (43.Rxe4 is well met by dxe4 44.Qg4+ Bg5!, and this last move would also have worked at this point in the game.)

43…Kxf7 44.Qh5+ Kg7 45.Qg4+ Kh6 46.Qf4+ Bg5 Finally White runs out of checks! 47.Qf7 Nf2+ 48.Kh2 Qc7+! 49.Qxc7 Rxc7 50.Re6+ A last try... 51…Kg7! No need to get mated on h5, breaking the heart of fans and teammates! White resigned. A multifaceted KID battle which shows that pushing ...f5 isn't Black's only way of creating activity - we can also work on the queenside, try to soften up White's dark squares by ...h5-h4 and so on. 0-1

Sawan Eman vs. Geske Bruna - A game fragment.

A topical line in the Sicilian Rossolimo led to this position, where White is certainly happy about the black king on f8. Black has just played ...Bd6-e5, trying to consolidate their defenses by ...d7-d6 next. Can you spot Eman's powerful reply with the White pieces?

16.Bf4! Development with tempo, while also trading off one of Black's main defenders. 16…Bd6 ( 16...Bxf4? 17.Qe7+ Kg8 18.Qe8+! was Eman's evident point. By the way, there is a nice Rossolimo game by Judit Polgar vs. Pavlina Chilingirova at the Thessaloniki Olympiad in 1988, which ended in a back rank mate after a queen sacrifice on f8.) ( 16...d6 is well met by 17.Bxe5 dxe5 18.Rad1 when d5-d6 can't be parried in a good way, e.g. 18...Qd6 19.Ne4 or Rd8 19.d6! Rxd6 20.Rxd6 ( 20.Qb4 also works) 20…Qxd6 21.Rd1 heading for d8.)

17.Rac1! The last friend to the party.

17…Qb6 18.Bxd6+ Qxd6 19.Ne4 The difference in overall activity is astonishing.

19…Qh6 (19...Qxd5 is well met by 20.Rcd1! Qc6 21.Rd6 getting Black's queen off the long diagonal so that the knight can move. At the same time, the d7-pawn turns into a target for White's pieces, e.g. Qc7 22.Red1 Bc6 23.Nf6! ( 23.Nc5 is a good alternative if we prefer less calculation) gxf6 24.Qh6+ Kg8 25.R1d3 Be4 26.Rxd7! Qc8 27.Qxf6 Bxd3 (else 28.Rd8+ next) 28.Qxf7#)

20.Qg4! Getting closer to the back rank. 20…Bxd5 21.Qxd7 Be6 22.Qb7 White's basically a rook up in an open position, so the rest is easy. 22…Re8 23.Nc5 g5.

24.Re3! A flexible attacking move, with ideas such as 25.Rce1 and 25.Rf3. Black now runs into a little tactical trick, but the position was difficult in any case.

24…Qf6? 25.Rxe6! The rook and pawn recaptures invite a knight fork on d7.

25…Qxb2 26.Rxe8+ Kg7 27.Ree1! Safety first. Black resigned. 1-0

GM Johan Hellsten & Katie Dellamaggiore, Marshall Spectator Contributors

Endgame Corner, by IM Silas Esben Lund

This column treats rook endgames with 3 pawns each on the kingside, where White has an extra pawn on the queenside. In both cases White has an a-pawn where the defending black rook is actively placed behind the pawn. These positions occur frequently in practice. The first position is a famous game example, not least due to the Kantorovich/Steckner debate. The other game example shows the dangers for Black if he is not able to generate counterplay with g6-g5. If not mentioned, the commentary in the following are by Dvoretsky, from his Endgame Manual. I have made a few comments on my own.

Illustrative Example

You can play through the positions in this article with annotations here.

1. Ra7 (After 1. Kd4 Rxf2 2. Rf8 Ra2 3. Rxf7+ Kg4) ( 1. f3 Ra3+ 2. Kd4 Rxf3 3. Rf8 Ra3 4. Rxf7+ Kg4 5. Rf6 Kxg3 6. Rxg6+ Kxh4 7. Kc5 Kh3 8. Kb6 h4 (both lines by N. Kopaev), Black's task is much easier.) (Lund: 1. a7 Kg4 In general, Black is aiming to get the king to g4 to create counterplay. In the next position, White was able to prevent this.)

1... f6 (1... Kf6 has been considered a prelude to an easy draw for many years. For example: 2. Kd4 Rxf2 (Lund: 2... g5 seems to draw, as I pointed out in Sharp Endgames (Quality Chess, 2017).) 3. Rc7 Ra2 4. a7 Kf5 5. Rxf7+ (However in 2003 the evaluation of this position was radically changed due to an excellent suggestion by J. Steckner: 5. Kc4 In case of Kg4 White wins after (If 5... Ra1 then 6. Kb5 and the threat of interposition can be neutralized only by means of a series of checks that helps the white king to advance: Rb1+ 7. Kc6 Ra1 8. Kb7 Rb1+ 9. Kc8 Ra1 10. Rxf7+ Kg4 White gains the missing tempo with 11. Rg7 Kxg3 12. Rxg6+ Kxh4 13. Kb7 Rxa7+ 14. Kxa7 Kh3 15. Kb6) 6. Kb3 Ra6 7. Rc4+ Kxg3 8. Ra4 Rxa7 9. Rxa7 Kxh4 Lund: This endgame is winning for White, and the highest priority is to bring the king to the kingside quickly. The greedy and time-consuming 10. Rxf7 only leads to a draw after Kg3) 5... Kg4 6. Kc5 Kxg3 7. Kb5 Rb2+ (7... Kxh4 8. Rf4+ Kg3 9. Ra4) 8. Kc6 Ra2 9. Kb7 Kxh4 10. Rf6 Rxa7+ with equality (V. Kantorovich).) Lund: To conclude - the king retreat to f6 does not lose as Black can still play 2...g5! The real mistake was to take on f2 after which White is indeed winning, following Steckner's line.

2. Ra8 (2. Kf3 is not dangerous for Black: after g5 3. hxg5 fxg5 4. Ra8 g4+ 5. Ke3 Kg6 his king returns to g7 in time.)

2... Kg4 3. a7 f5 4. Rg8 Lund: The king is on g4 gives Black plenty of active counterplay. (4. Kd4 Kf3)

4... f4+ 5. gxf4 (5. Ke4 Ra4+ 6. Ke5 Ra5+) 5... Ra3+ 6. Ke4 Ra4+ 7. Ke5 Ra5+ 8. Ke6 Ra6+ 9. Kf7 Rxa7+ 10. Kxg6 Ra6+ 11. Kf7+ Kxf4 (M. Dvoretsky) *

Unzicker, Wolfgang v. Lundin, Erik

This game example, also from Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual, is a good illustration of how Black can get trapped in a seemingly ideal position for counterplay with f6 + Kf5: but where he is unable to push g6-g5.

48. f3+ (48. a7 Ra2+ allows the Black king to f3.) 48... Kf5 (48... Rxf3 49. a7 Ra3 50. Re8+ followed by pawn promotion.)

49. a7 Black is now unable to launch the counterplay with g6-g5, and is therefore doomed to passivity. White can bring the king to h6 (with a few tricks on the way) and then transform the position to win.

49…Ra2+ 50. Kd3 Ra1 51. Kd4 Ra5 52. Kc4 Ra3 53. Kc5 Dvoretsky: "When Black's pawn stands on f7, his king can return to f6 or g7 with an absolutely drawn position." That is one reason for not moving the pawn on f7.

53…Ra1 54. Kd6 Ra3 (As Dvoretsky points out, the squares a6 and f7 are corresponding. The following line shows that: 54... Ra6+ 55. Ke7 Ra5 56. Kf8 Ra6 57. Kf7)

55. Ke7 (55. Rc8 is a pretty tactic that White missed: Ra6+ 56. Rc6 Rxa7 57. Rc5#)

55... Ra6 56. Kf7 The rook now has to move away from the defence of f6. 56…Ra3 57. Kg7 Ra1 (57... g5 58. hxg5 Kxg5 59. Kf7 Kf5 (59... Z0 Threatening 60. Rg8+) 60. g4+ hxg4 61. fxg4+ White wins after Kf4 62. Kxf6)

58. Kh6 Ra6

With the king on h6, White wins with the following transformation: 59. Rb8 Rxa7 60. Rb5+ Ke6 61. Kxg6 This is a 3 vs 2 pawns on the same side that is winning for White. Black's pawns are split and vulnerable, and the black king sidelined. 61…Ra8 (61... Ra3 62. Rf5) 62. Kxh5 Rg8 63. g4 Rh8+ 64. Kg6 Black resigned due to 64…Rxh4 65. Rh5 with a rook exchange. (65. Rb6+ Ke7 66. Rxf6 with two extra pawns.) 1-0

IM Silas Esben Lund, Marshall Spectator Contributor

Revisiting Frank Marshall, in an Enjoyable New Book

Frank J. Marshall, the founder of our club, shares center stage in a new review of chess in the first decade of the 20th century, the period when he rocketed to stardom, displaying all of his talents and shortcomings. The result was spectacular success mixed with conspicuous failure.

In the pleasurable ‘’A Century of Chess -- Book 1: 1900-1909,’’ authors led by Marshall Chess Club member Sam Kahn call those years ‘’a watershed decade’’ when professional players were displacing amateurs and advancing a more-scientific approach, including the premise that attacks must be prepared by building strong positions. ‘’This was the peak of classicism—and many of the precepts of how beginners are introduced to chess were really worked out right around this time,’’ according to the book (CarstenChess, 286 pages, $27.99 on Amazon for the print edition). The world champion was Emanuel Lasker. Other leading lights at the start of the decade included Harry Pillsbury and Geza Maroczy, competitors still celebrated today.

Marshall, born in New York in 1877, was already a formidable player when the new century began. At a tournament in Paris in 1900, before his 23rd birthday, he tied for 3rd place, topped only by Lasker and Pillsbury. ‘’A Century of Chess’’ shows 41 memorable games, with notes mainly by International Master Cyrus Lakdawala, a deft and amusing commentator. Included are 10 played by Marshall, more than by any other player save David Janowski of Poland, also with 10. Readers first encounter Marshall facing Georg Marco of Austria, at Monte Carlo, Monaco, in 1904. Marshall is described as ‘’one of the greatest confusers/swindlers in chess history,’’ a player who often popped out of lost positions and restored winning chances. In this game, after Marco missed an easy win in the middlegame, Marshall unleashed brilliant tactics and triumphed after a lengthy endgame.

Next, from the same tournament, readers see Marshall playing Maroczy, the Hungarian remembered today for the “Maroczy Bind’’ pawn formation against the Sicilian. After losing a tempo as white in the Queen’s Gambit Declined opening, Marshall attacked anyway. Marozcy had to dodge “a vile swindle attempt’’ in which Marshall tried to set up a smothered mate. No such luck, yet Marshall continued to play rashly, choosing a time-wasting knight maneuver with toothless threats instead of doubling rooks on the only open file. Soon he eschewed a perpetual check and blundered. Maroczy -- whom Marshall greatly admired, once calling him ‘’the greatest living master of chess’’-- collected the win.

Marshall was in better form – probably the best of his career, which lasted decades-- at the 1904 tournament in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, in which he went undefeated over 16 rounds and placed clear first, scoring 13 points, two ahead of the next two finishers, Janowski and Lasker. The book shows his 76-move game as black over Janowski, who missed the chance to unleash a winning attack on move 24 and later enabled Marshall to exchange queens, gain the advantage and win. No Marshall trickery was needed at Cambridge Springs, just solid moves and clear thinking in complex positions. According to the authors, it was at Cambridge Springs that Marshall’s reputation peaked. He began to be seen as a potential contender for the world title, but later in the decade his limitations came to the fore. Others, notably including the emerging star Jose Capablanca of Cuba -- who would go on to become world champion in the 1920s -- played more accurately.

Marshall got away with a questionable opening in the eighth game of a 1905 match in Paris. His opponent, Janowski, put a knight on the rim, trying to hold an extra pawn on the queenside. He was met by both a kingside attack and Marshall’s dangerously advancing queen pawn, and had to resign after 30 moves. But at Ostend, Belgium, also in 1905, another poor opening by Marshall was punished by Maroczy, who seized first one pawn and later another. Marshall was caught in a losing rook ending -- not without complications, as both sides marched pawns forward and obtained new queens -- and his resignation came after 58 hard-fought moves.

Another tough opponent that year was the German Siegbert Tarrasch. In the seventh game of a match in Nuremberg, Germany, Tarrasch missed a winning idea, according to the notes, taking command anyway after an immediate Marshall error. In a rook ending, playing a pawn down and with an inferior king position, Marshall resigned. His opponent was about to obtain the deadly Lucena position that ensures victory in such circumstances.

The book also shows Marshall battling, in the second game of a 1907 match, another German -- the fierce Lasker, the decade’s premier player (whom Marshall had beaten at Cambridge Springs). This time, Marshall had no trouble equalizing as black in a French Defense, and a wild game with opposite-side castling ensued. But after sacrificing a pawn, he failed to get compensation. ‘’Marshall’s dirty tactical tricks fail to confuse the king of dirty tactical tricks,’’ the notes say after move 27. Lasker simplified into a knight ending and mercilessly outplayed his opponent, collecting the point.

For Marshall, the worst was yet to come. In 1909, he entered a match with Capablanca, then only 20 years old and deemed the underdog. Shockingly, Marshall collapsed, losing eight games while winning just one (there were also 13 draws). Capablanca displayed “overwhelmingly superior strategic ability, coupled with superior defensive/counterattacking skills,’’ making Marshall’s attacks “appear amateurish by comparison.’’

Readers are shown three of those Marshall losses. In game two of the match, Capablanca, playing white, ignored an attack on his queen, knowing it would be poison to capture, and accelerated an assault on Marshall’s king, leading to resignation. Game five, described as ‘’a masterpiece that remains untouched by time,’’ featured a series of sharp and beautiful tactics by Capablanca, who delivered a checkmate as black after Marshall, with an extra queen but dead lost, failed to resign. In game 11, Marshall, playing white, audaciously placed a bishop on a square covered by a black pawn, daring his opponent to take it. While this was “a classic Marshall bluff,’’ according to the annotation, the coolheaded Capablanca couldn’t be fooled. He took the piece, and the game.

As readers of this article may realize by now, Marshall won only three of his 10 games seen in this book. But even his losses can be fascinating to study. His combativeness often forced opponents to play brilliantly. The authors, whose aim was to showcase multiple players, benefited from this selection of games even if different ones might leave a more-favorable impression of Marshall’s prowess.

With his frequently romantic, even coffeehouse moves and the consequent travails, Marshall isn’t an ideal exemplar of the march toward more-scientific play. In any case, by focusing on just one decade, the authors catch neither advances made earlier than 1900 nor those that came after 1909. The book is less successful as an overview of the evolution of chess strategy than as a trove of instructive and enjoyable games and vignettes. All of the featured battles, including the 31 in which Marshall didn’t take part, are gems, enhanced by sparkling new notes.

While doing little to revise previous judgments of Marshall and his rivals, this book is a fine introduction to the era. It shows evidence of why Marshall has remained a leading figure in U.S. chess history and, alas, how he fell short of the level of play needed for rising to world champion.

Note: Jeffrey Tannenbaum is the treasurer of the Marshall Chess Club and a collector of chess books.

Jeffrey Tannenbaum, Marshall Spectator Contributor

Chess Toons

En Passant

Hurricane Helene cut a path of destruction across the Southeastern United States, taking out power for millions, destroying homes, lives, and also taking down the USChess Servers causing a delay in tournaments being rated.

India won the Open and Women’s Olympiads in Budapest, while for the first time in history no European team reached the podium in either event.

GM Ian Nepomniachtchi won the 10th edition of the Gashimov Memorial on Saturday in Susha, Azerbaijan. The Russian grandmaster, who played in the tournament for the first time, finished ahead of GMs Nodirbek Abdusattorov and Shakhriyar Mamedyarov.

Cuban champion Luis Ernesto Quesada will try today to maintain his solitary leadership in the Ibero-American Chess Championship of Linares 2024.

To mark FIDE’s centenary and International Chess Day, the FIDE100 Art Contest inspired artists of all ages from around the world to express their passion for chess through creative mediums. The competition attracted 271 entries from 54 countries, with participants ranging from professional to young aspiring artists, including the youngest entrant, just four years old. Uzbekistan submitted the highest number of entries, with 78 artworks, showcasing the global appeal of the event.

Problems, Problems, curated by Alexander George

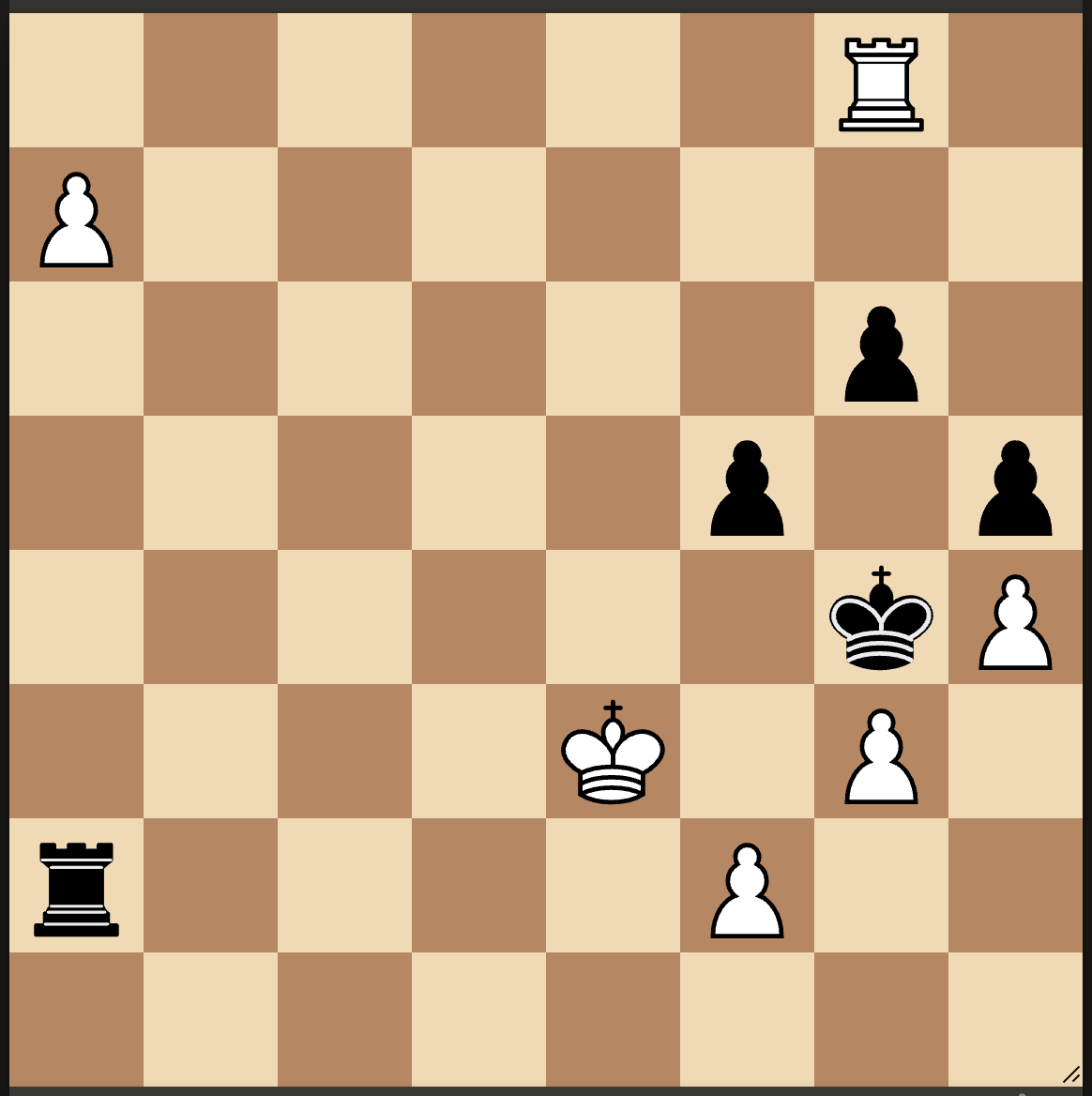

J. Beasley, 1999

White to move and win.

White against lone king cannot force a mate with two knights. However, surprisingly, White can sometimes do so if Black has a pawn! Composers have been fascinated by this. One of the nicest demonstrations of this I know is the above problem by the British composer, John Beasley, who died earlier this year. You can read a little about him here. More from Beasley next week.

---

Last issue’s puzzle, S. Loyd, 1868

White to move and win.

Solution to last week’s puzzle: 1.Bd7+ Ka3 2.Bc6 Ka2 3.Kc2 a6 4.Bh1 draw.

---

Alexander George

Editor's Note

As always, if you have any feedback, comments, or would like to submit an article please contact us directly at td@marshallchessclub.org.

Enjoy, and thanks for reading!

The Marshall Chess Club

23 West Tenth Street New York, NY 10011

212.477.3716

Thanks for reading The Marshall Spectator! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support the club.

Thank you. Looking forward to visiting.